Immunity Passport — Part 1: Exploration

Everyone is talking about them. Some claim they will save the economy, others fear they might divide the world into two classes: the immunes and the non-immunes. In this post, we’ll explore the topic of immunity passports in the context of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

What’s an immunity passport?

An immunity passport is a document that indicates whether a person is immune or not to a disease. In this context, the disease is COVID-19. It can take the form of a physical paper document, a mobile application, or a database in which your ID is tied to your immunity status. Here, we’ll use the term “immunity passport” because it’s the one that best captured our global imagination. You’ll hear people use “immunity cards”, “immunity certificates” and “risk-free certificates” to refer to the same idea.

Searches for “immunity passport” vs “immunity certificate” vs “immunity card” (via Google Trend)

Searches for “immunity passport” vs “immunity certificate” vs “immunity card” (via Google Trend)

Why do some people think we need an immunity passport?

Many have argued that confining people who are immune to COVID-19 serves no purpose, and only hurts the economy. They believe that immune people should go back to their normal life and participate in the economy. They shouldn’t be confined, they shouldn’t have to wear masks, and they shouldn’t be forced to respect social distancing. They should be allowed to travel. They should be given priority when applying for high-risk (COVID-19 wise) jobs such as interacting with confirmed cases or taking care of the elderly.

Without some kind of immunity passport, it would be very difficult to differentiate those who are immune and those who aren’t, effectively preventing these restrictions from being lifted and these privileges from being granted.

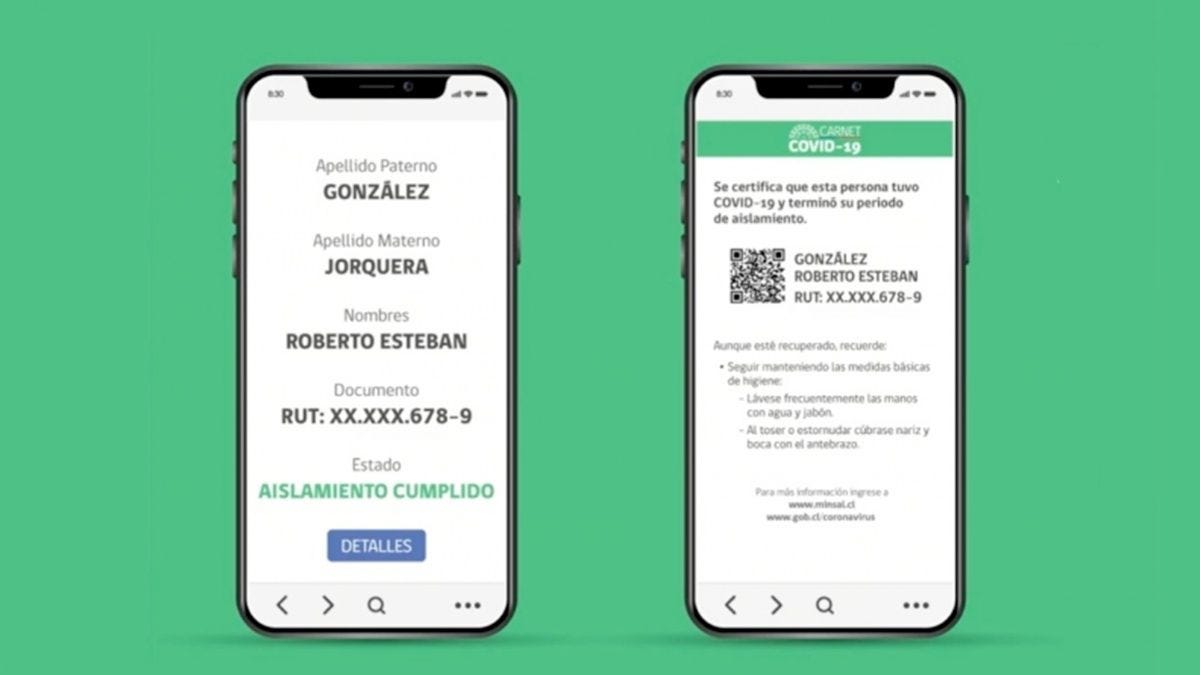

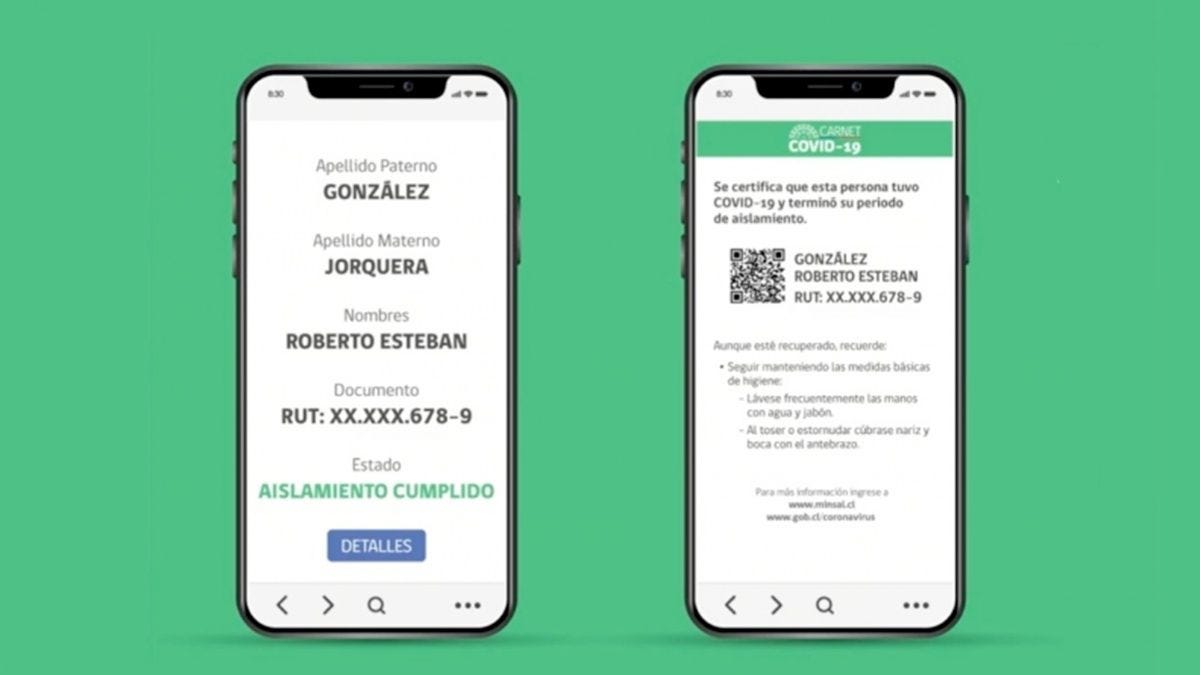

Some countries, including the US, the UK, Italy, and Germany, are already considering the idea. Chile is expected to be the first country to issue such passports, which they call “Carnet Covid”, to those who have recovered from the disease.

Chile’s “Carnet Covid”

Chile’s “Carnet Covid”

Why are some people opposed to immunity passports?

Many scientists believe that it’s too early to issue immunity passports. They claim that we don’t know enough about the virus to determine whether (and how long) people who have recovered are protected against re-infection. The World Health Organization recently published their concerns about immunity passports.

There is currently no evidence that people who have recovered from COVID-19 and have antibodies are protected from a second infection.

― World Health Organization

Others believe that even if we had a reliable way to determine whether someone is immune or not to COVID-19, we still shouldn’t issue immunity passports. They fear that it would introduce a new class division in society: the immunes and the non-immunes. If anything, it might make things worse, as people would be encouraged to seek out the virus in ways reminiscent of pox parties.

Privacy concerns are also on the mind of many, who worry that immunity passports might infringe on their privacy and introduce new precedents that might not be reverted once the pandemic is over. Many had echoed similar concerns regarding contact-tracing apps, fearing that they would open the door to a China-style surveillance state.

Where would immunity passports be required?

Immunity passports might be required in scenarios where a person would interact with infected people (e.g., doing triage in an emergency room) or interact with vulnerable people (e.g., volunteering in a nursing home). They might also be required when using public transportation, going to the gym, donating blood, preparing food, or traveling between different cities/regions.

Countries might also ask visitors for proof of immunity at their border, which many already do for yellow fever. Airlines and hotels might require digital proof of immunity to book flights and rooms.

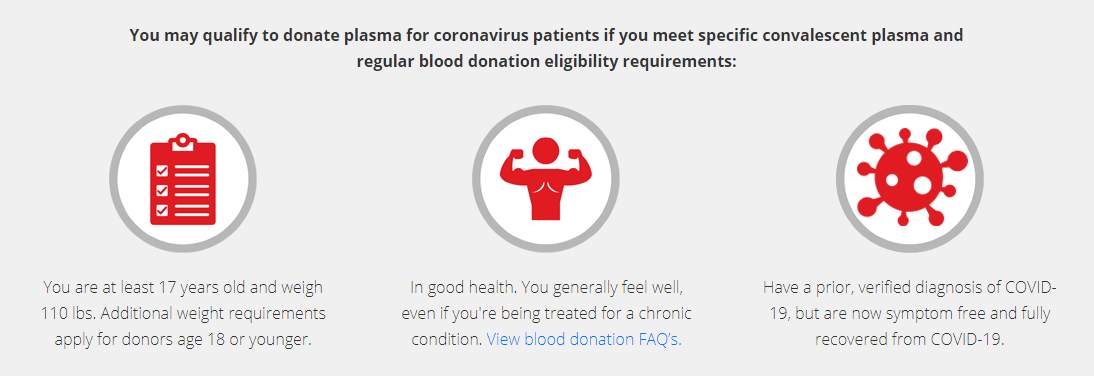

The American Red Cross is already requesting plasma donations from recovered COVID-19 patients.

Requirements to donate plasma for coronavirus patients (via American Red Cross)

Requirements to donate plasma for coronavirus patients (via American Red Cross)

How would immunity be determined?

We still don’t know enough about COVID-19 to tell if immunity is possible and how long it could last. Studies on SARS-CoV, the closely related virus responsible for 2003’s SARS outbreak, determined that its antibodies offer protection for roughly two to three years. More time and research will be necessary to know whether we can expect the same from SARS-COV-2.

However, we can already identify 3 typical scenarios from which we could infer a person’s immunity:

-

A person has symptoms, tests positive for COVID-19 (typically via RT-PCR), and then recovers.

-

A person has no symptoms and tests positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (typically via IgM/IgG immunoassay).

-

A person receives a COVID-19 vaccine.

As we learn more about COVID-19, we will be better equipped to predict how much immunity each of these scenarios confer to their subjects. It will be important to keep track of all details ' such as the severity of symptoms, the testing method, and a device’s manufacturer/lot number ' as they could influence the scale and validity of these predictions. For example, a person with severe symptoms might have longer-lasting immunity than a person who never had symptoms.

Don’t immunity passports already exist?

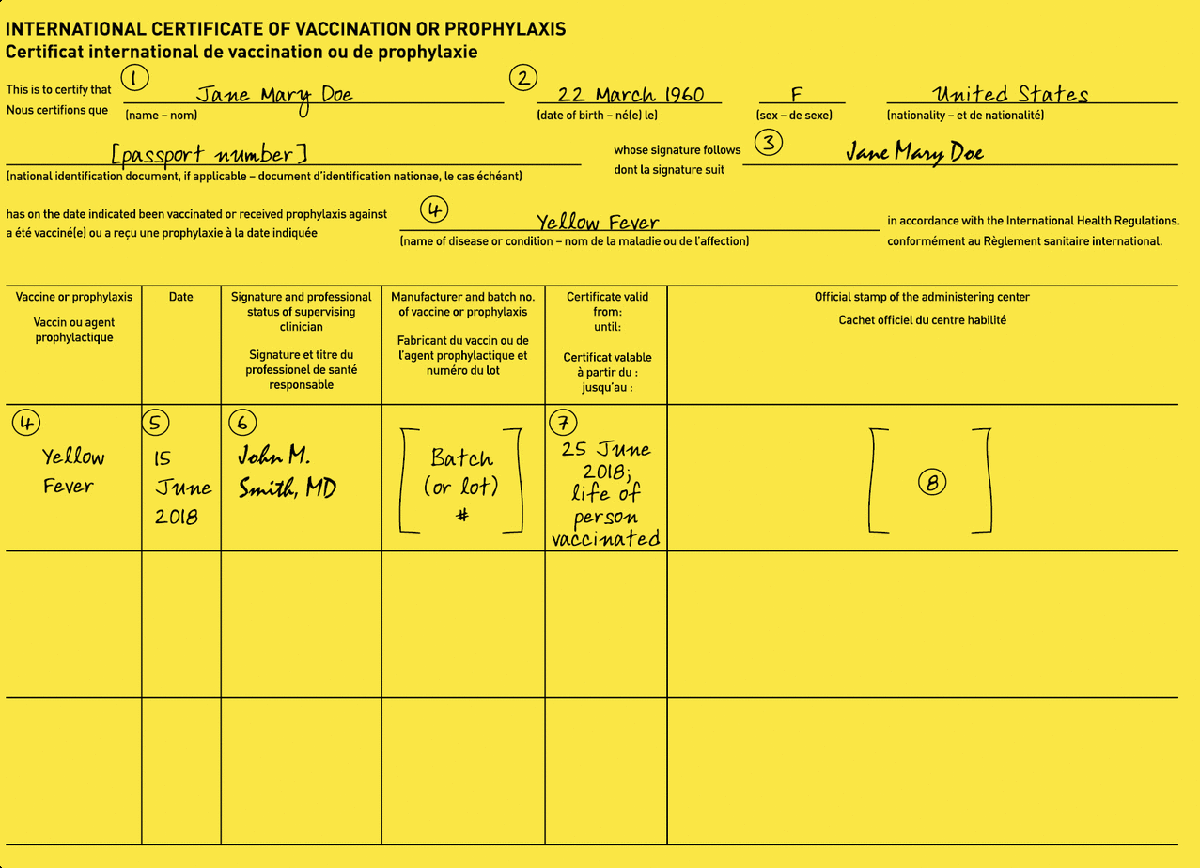

The idea of an immunity passport isn’t new. In fact, they already exist and we still use them every day. The best example is the International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (ICVP), which is issued by the World Health Organization and is mostly used as a proof of yellow fever vaccination (which is mandatory to enter many countries).

International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (via CDC)

International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (via CDC)

In 2016, a team of researchers published a paper called Travel Vaccines Enter the Digital Age: Creating a Virtual Immunization Record, in which they explore the idea of a virtual immunization record, which could complement or replace the ICVP.

Screenshots from Travel Vaccines Enter the Digital Age: Creating a Virtual Immunization Record

Screenshots from Travel Vaccines Enter the Digital Age: Creating a Virtual Immunization Record

What about immunity passports for COVID-19?

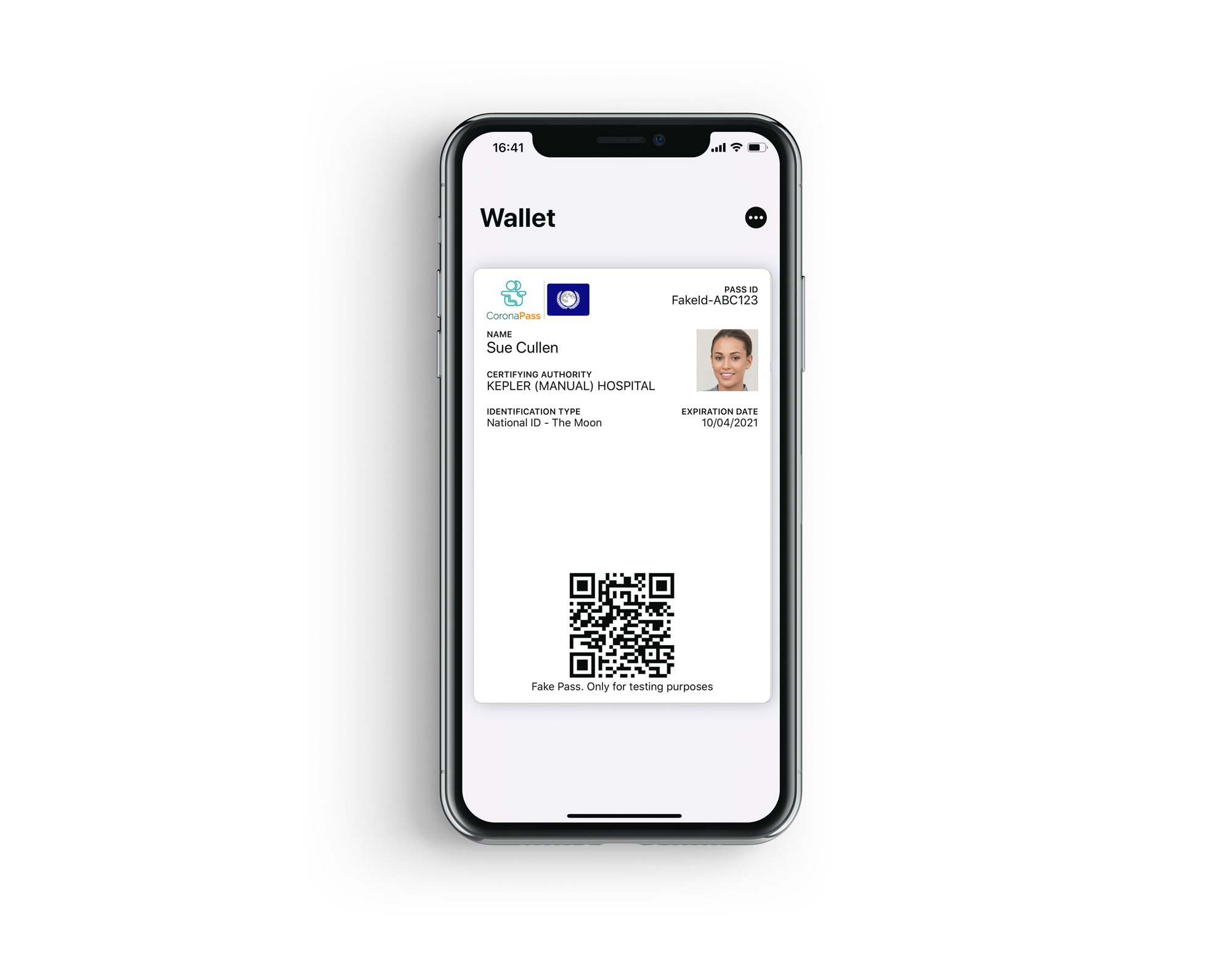

While the ICPV could be used as proof of COVID-19 vaccination, and maybe even allow for antibody test results to serve as proof of immunity, many teams around the globe have been working on immunity passports dedicated to COVID-19. Interestingly, they’re almost exclusively digital. I hope you don’t mind QR codes.

Here are a few of them:

CoronaPass by Bizagi

CoronaPass by Bizagi

Carnet Covid (Chile)

Carnet Covid (Chile)

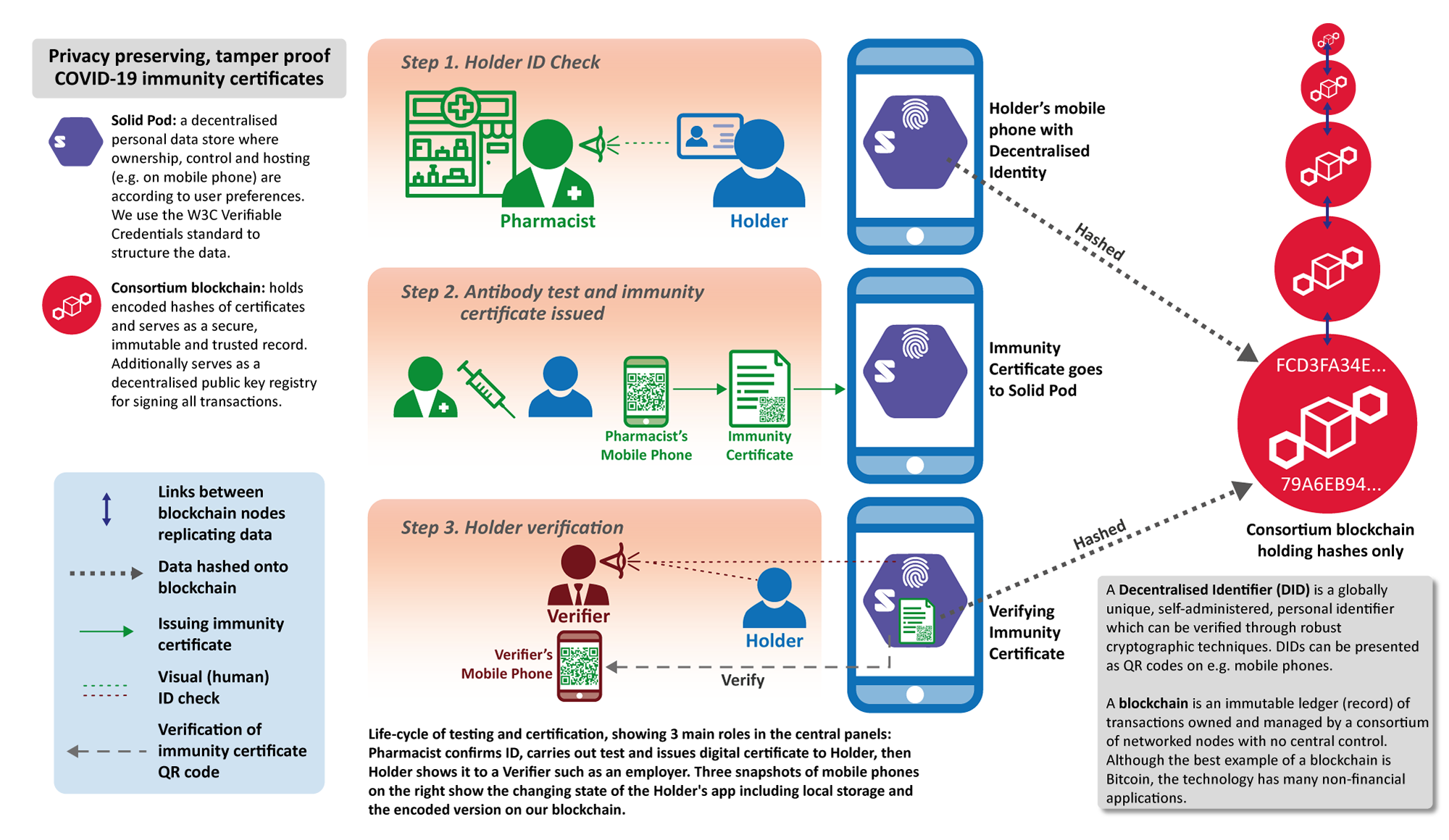

COVID-19 Antibody Test Certification by OpenUniversity’s Knowledge Media Institute (UK)

COVID-19 Antibody Test Certification by OpenUniversity’s Knowledge Media Institute (UK)

Immuno Lynk by MIT (USA)

Immuno Lynk by MIT (USA)

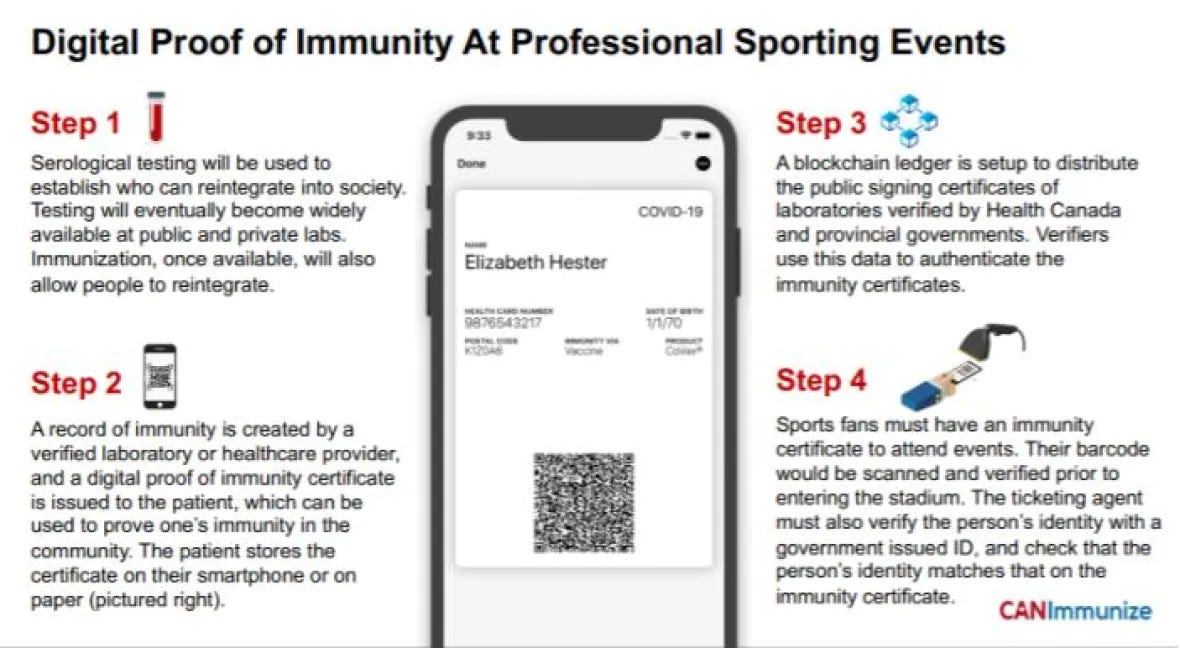

CANImmunize (Canada)

CANImmunize (Canada)

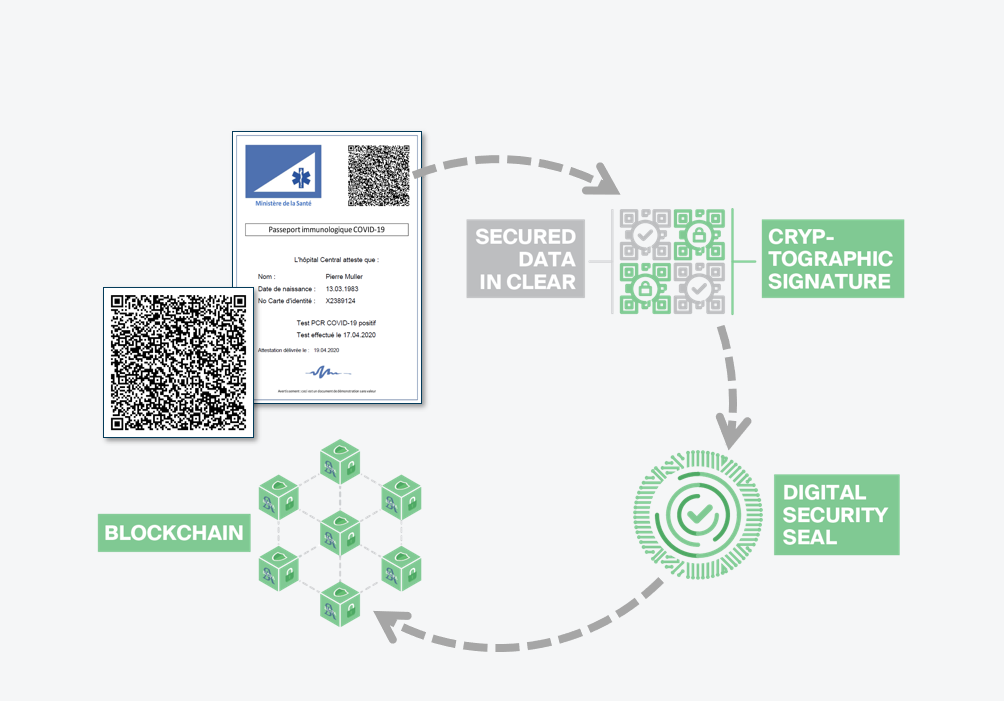

CERTIS by SICPA (France)

CERTIS by SICPA (France)

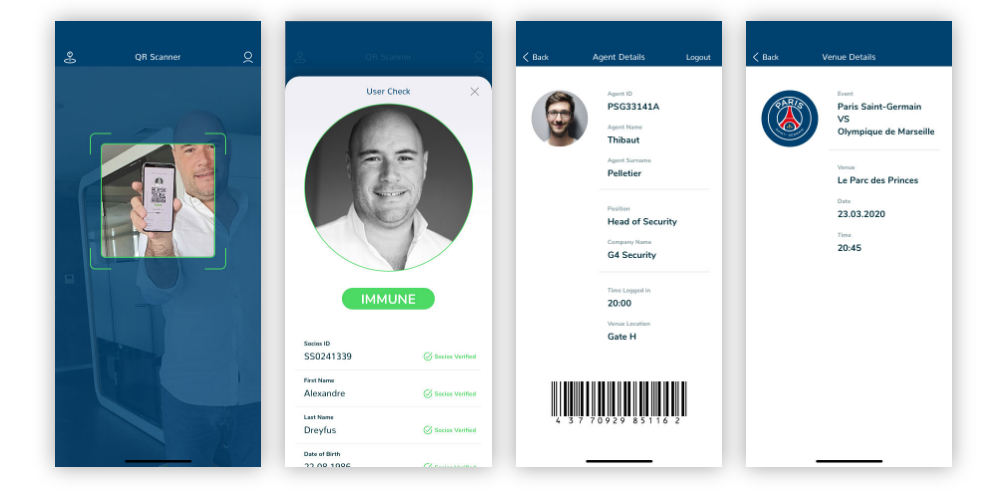

Socios Pass by Socios

Socios Pass by Socios

Sacyl Conecta (Spain)

Sacyl Conecta (Spain)

These are just a few of the many COVID-19 immunity passport projects out there. Some are proofs of concepts, while others are actively being implemented. As far as I can tell, none of them are currently deployed and used as immunity passports, but it shouldn’t take too long before that happens. We should expect to see more of these projects pop up in the coming weeks.

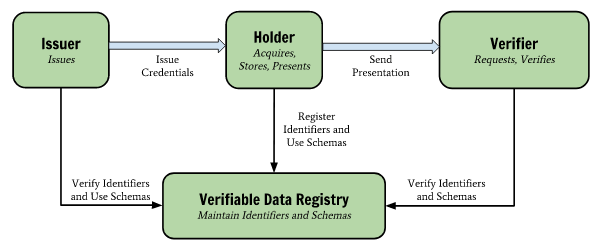

Perhaps the most promising effort towards an immunity passport comes from the Covid Credentials initiative (CCI), a collaboration of 60+ organizations working together to solve this problem using the W3C industry standard called Verifiable Credentials. If you think you can contribute, you’re invited to join one of their many workstreams.

Verifiable Credentials' roles and information flow (via Verifiable Credentials)

Verifiable Credentials' roles and information flow (via Verifiable Credentials)

Are there alternatives to immunity passports?

China has been conducting what is by far the largest and most successful contact-tracing experiment for months already. Their solution, known as the AliPay Health Code, has been deployed in over 200 cities in China. If you want to move around, you’ll need to install the app. It’s mandatory.

AliPay Health Code (via The New York Times)

AliPay Health Code (via The New York Times)

Unlike an immunity passport, which gives freedom of movement to those who are immune, the AliPay Health Code uses artificial intelligence to calculate how likely someone is to be infected based on their history and personal data. Then, it gives them a colored QR code that indicates their health status: green, yellow, or red. In many cities, such as Wuhan, you need a green code to be allowed on public transport. With a red code, you might not be welcome anywhere other than the hospital.

While the algorithm is kept secret, we know that the application continuously tracks the user’s location over time to perform contact tracing. Yet, no one really understands how it assigns color codes to people. Many have claimed that their color code had changed, for example from green to yellow, without understanding why, and definitely without being given an explanation. Overall, Chinese people still seem to embrace the system and believe it to be a key, along with universal mask-wearing, to China’s rapid recovery and today’s low transmission rate.

Other countries also have contact-tracing apps, but none of them prescribe where you can and can’t go to near the same extent as AliPay Health Code.

What’s with all the apps and QR codes? Can’t we just use the International Certificate of Vaccination and Prophylaxis?

While the ICVP perfectly served its purpose since its introduction in 2005, it’s not clear that it’s the best solution in the context of a global pandemic in 2020.

Here are some criticisms of the ICVP:

-

Physicality: It’s one more thing to carry. It can’t be issued or verified online. It can be forgotten or lost. It can’t be backed-up.

-

Size: It’s meant to be carried in a passport. It’s too big to fit inside a wallet.

-

Durability: It’s made from cardboard. It’s not durable enough to be used daily. It can easily get damaged if wet.

-

Authenticity: It uses signatures and stamps, which motivated individuals could fake.

-

Verification: It’s handwritten, which makes it slow to read and verify.

-

Mutability: Its content can’t be updated or revoked (as we learn more about COVID-19 immunity).

Here are some of the benefits of the ICVP:

-

It already exists.

-

It’s simple (no QR codes, no cryptography, no public key registry).

-

It’s proven and well understood (at least at some international borders).

-

It’s flexible (you can repurpose the boxes for other things like antibody testing, you can write notes).

-

It’s accessible (people don’t need to use or understand technology).

-

It’s reliable (you don’t need to worry about bugs, connectivity, or battery).

-

It’s private (doesn’t require a database with personal information).

It’s possible that many of the problems with the current ICVP could still be solved in a low-tech way. Perhaps we could issue a laminated credit card size version of the ICVP, or put a tamper-proof immunity sticker on people’s identity cards. Some have talked about immunity bracelets, which was the chosen solution in the movie Contagion (2011). Unlike most other solutions, immunity bracelets have the advantage of being immediately visible, which might facilitate the otherwise awkward situations where people don’t know each other’s immunity status.

Immunity bracelet from Contagion (2011)

Immunity bracelet from Contagion (2011)

However, if the privileges given to the immunes are great enough to compromise the security and authenticity of low-tech immunity passports, then we’ll have to turn to a digital approach, which is where apps and QR codes come into play.

What makes digital immunity passports more secure than physical immunity passports?

To verify the authenticity of a physical document, you usually look for physical characteristics that would be difficult to counterfeit. For example, banknotes often have security features such as seals, microprinting, raised printing, etc. On an ICVP, the only security features are a handwritten signature (which you usually can’t verify) and a stamp (which is hard but not impossible to fake).

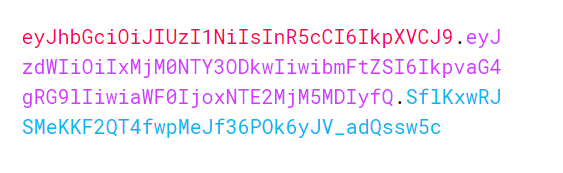

To verify the authenticity of a digital document, you only need to look at the digital signature. Without going into the details of public-key cryptography, a digital signature mathematically proves the integrity (the document hasn’t been tampered with) and the authenticity (only the person knowing the secret key associated with the signature could have signed it) of a document. Assuming that secret keys have been kept secret (which is in the interest of authenticating authorities), no amount of effort could produce a fake signature. This is the same technology used to secure Bitcoin, which has a total market cap of over $100 billion.

JSON Web Token with an HMAC-SHA256 digital signature (in blue)

JSON Web Token with an HMAC-SHA256 digital signature (in blue)

Unlike physical signatures, which humans can intuitively understand, digital signatures only make sense to machines. If you were to verify a digital signature by hand, on paper, it could take you years. A machine, on the other hand, can do it in a fraction of a second. That’s why we use computers to verify digital signatures. In a COVID-19 immunity passport scenario, the computer would typically be the smartphone carried by the verified.

Let’s imagine you’re about to take an international flight. Before you’re allowed on board, an airline employee might ask you for proof of immunity. They’re holding a smartphone and they need your immunity passport’s digital signature. One way to do it would be to have the employee take a few minutes to type out the entire case-sensitive chain of character (possibly thousands of characters long) on a tiny on-screen keyboard. God forbid they make a typo. Another way is to scan a QR code, which takes just a second. This explains why most of the proposed digital immunity passports feature a prominent QR code. A QR code is nothing more than a neat way to transfer some text to a device using a camera.

A QR code that contains the text “Hello world!"

A QR code that contains the text “Hello world!"

When can I expect to receive my immunity passport?

While Chile is expected to issue immunity passports in the coming days, you might never actually receive yours. Technical and ethical challenges are slowing down their release, and some have predicted they would never see the light of day. If we’ve learned anything about them, it’s that they’re controversial and hard to get right.

Considering that COVID-19 vaccines are thought to be at least 18 months away and that the World Health Organization doesn’t endorse antibody presence as proof of immunity, we might actually have to wait a while, perhaps until we don’t need them anymore.

What’s next?

In my next post, I will propose a technical specification for a digital immunity passport.